Jene Bramel

Footballguy

IDP 401 – The 3-4 front

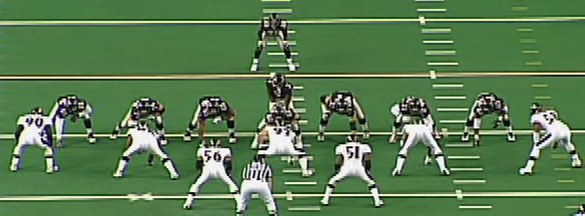

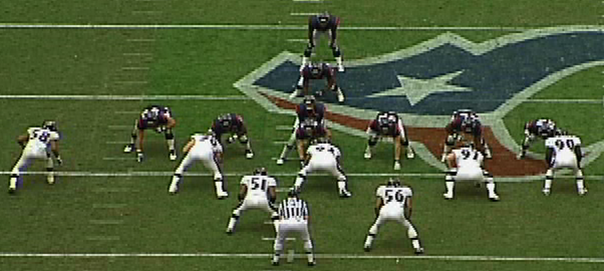

We'll continue the Discussing Defensive Schemes series this week with a look at the 3-4 front, which has arguably become the hottest defensive trend in the NFL today. It’s not quite that simple, though. Just as there are multiple variations of the 4-3 front – Tampa-2 underfronts and zone coverage, ‘Miami’ fronts and aggressive gap attack philosophies, gap control read-and-react schemes, etc – there are different philosophies of the 3-4.

Since some of you have expressed an interest in how today’s defensive fronts developed, we’ll use this first post to add a little historical flavor to our discussion. It’s probably not a stretch to suggest that most think of Lawrence Taylor or the Pittsburgh Steeler zone blitz concept first when someone mentions the 3-4 front. In truth, the 3-4 in the NFL has a much richer history than that.

Unlike the 4-3, which was first designed and successful in professional football, the 3-4 got its start at the University of Oklahoma in the 1940s (and probably sooner -- no pun intended). It wasn’t until the mid-1970s, when teams were looking for ways to contain big speedy running backs and combat the downfield passing schemes that were gaining favor, that the 3-4 took hold in the NFL as an every down defense. Two teams began the revolution, but did it in very different ways.

The Patriots, under former Oklahoma coaches Chuck Fairbanks and Hank Bullough, used a two gap concept on the line, preferring to contain offenses rather than risk an overly aggressive philosophy. Meanwhile, the Oilers were running a much more aggressive, one gap 3-4 under head coach Bum Phillips. By 1980, almost three quarters of the defensive schemes in the NFL had three down linemen. And, like today, plenty of variations developed on the base 3-4 theme.

There were the aggressive Oilers and Saints under Bum Phillips, the Dome Patrol under Jim Mora in New Orleans, the opportunistic, swarming 3-4 schemes of the Dolphins’ No Name and later Killer “Bs”, the not-as-aggressive-as-you’d-think New York Giants of Bill Parcells and Lawrence Taylor, the (original) multiple front schemes of the Orange Crush in Denver and others. Though the philosophies and tendencies varied, the underlying concepts that made the 3-4 popular were the same.

The 3-4 gave coordinators the flexibility to blitz or drop into coverage without changing personnel. Versatile linebackers like Lawrence Taylor or Robert Brazile or Rickey Jackson or Ted Hendricks could rush the passer or drop into coverage effectively. Teams could disguise their blitzes and coverages easily and disrupt the timing and rhythm of the passing attacks that had taken over the league. The outside linebackers could walk up to the line of scrimmage and create a five man front of sorts to help contain the big, quick running backs of the day. Guys like OJ Simpson or Franco Harris found it a little more difficult to get outside against the 3-4.

Not surprisingly, the flexibility of the 3-4 front is driving its resurgence today. While there’s no question that the “scarcity” of the scheme is part of the reason for its current success, the versatility of the 3-4 makes is attractive when defending the pass-heavy attacks of today’s offenses.

Although it’s an artificial construct, we’ll divide today’s 3-4 fronts into three families for our discussion. Nearly all of the 3-4 coordinators in the league today draw concepts from each philosophy (i.e. most teams use both 2-gap and 1-gap alignments), but we’ll pigeonhole some recent teams into a given “family” for effect. Over the next few posts, we’ll look at the differences between the 1-gap and 2-gap 3-4 philosophies, and discuss the multiple front and zone blitz philosophies that grew out of the 3-4 front.

Next Up: What Charlie Weis called the only true 3-4

We'll continue the Discussing Defensive Schemes series this week with a look at the 3-4 front, which has arguably become the hottest defensive trend in the NFL today. It’s not quite that simple, though. Just as there are multiple variations of the 4-3 front – Tampa-2 underfronts and zone coverage, ‘Miami’ fronts and aggressive gap attack philosophies, gap control read-and-react schemes, etc – there are different philosophies of the 3-4.

Since some of you have expressed an interest in how today’s defensive fronts developed, we’ll use this first post to add a little historical flavor to our discussion. It’s probably not a stretch to suggest that most think of Lawrence Taylor or the Pittsburgh Steeler zone blitz concept first when someone mentions the 3-4 front. In truth, the 3-4 in the NFL has a much richer history than that.

Unlike the 4-3, which was first designed and successful in professional football, the 3-4 got its start at the University of Oklahoma in the 1940s (and probably sooner -- no pun intended). It wasn’t until the mid-1970s, when teams were looking for ways to contain big speedy running backs and combat the downfield passing schemes that were gaining favor, that the 3-4 took hold in the NFL as an every down defense. Two teams began the revolution, but did it in very different ways.

The Patriots, under former Oklahoma coaches Chuck Fairbanks and Hank Bullough, used a two gap concept on the line, preferring to contain offenses rather than risk an overly aggressive philosophy. Meanwhile, the Oilers were running a much more aggressive, one gap 3-4 under head coach Bum Phillips. By 1980, almost three quarters of the defensive schemes in the NFL had three down linemen. And, like today, plenty of variations developed on the base 3-4 theme.

There were the aggressive Oilers and Saints under Bum Phillips, the Dome Patrol under Jim Mora in New Orleans, the opportunistic, swarming 3-4 schemes of the Dolphins’ No Name and later Killer “Bs”, the not-as-aggressive-as-you’d-think New York Giants of Bill Parcells and Lawrence Taylor, the (original) multiple front schemes of the Orange Crush in Denver and others. Though the philosophies and tendencies varied, the underlying concepts that made the 3-4 popular were the same.

The 3-4 gave coordinators the flexibility to blitz or drop into coverage without changing personnel. Versatile linebackers like Lawrence Taylor or Robert Brazile or Rickey Jackson or Ted Hendricks could rush the passer or drop into coverage effectively. Teams could disguise their blitzes and coverages easily and disrupt the timing and rhythm of the passing attacks that had taken over the league. The outside linebackers could walk up to the line of scrimmage and create a five man front of sorts to help contain the big, quick running backs of the day. Guys like OJ Simpson or Franco Harris found it a little more difficult to get outside against the 3-4.

Not surprisingly, the flexibility of the 3-4 front is driving its resurgence today. While there’s no question that the “scarcity” of the scheme is part of the reason for its current success, the versatility of the 3-4 makes is attractive when defending the pass-heavy attacks of today’s offenses.

Although it’s an artificial construct, we’ll divide today’s 3-4 fronts into three families for our discussion. Nearly all of the 3-4 coordinators in the league today draw concepts from each philosophy (i.e. most teams use both 2-gap and 1-gap alignments), but we’ll pigeonhole some recent teams into a given “family” for effect. Over the next few posts, we’ll look at the differences between the 1-gap and 2-gap 3-4 philosophies, and discuss the multiple front and zone blitz philosophies that grew out of the 3-4 front.

Next Up: What Charlie Weis called the only true 3-4

), we’ll have one more thread discussing some concepts that don’t fit easily into any of the earlier threads. It’ll be a catch-all thread, starting out with a post or three about the 46 scheme and some discussion of nickel defenses. After that, I’ll probably open a Q&A/request thread to tie up any loose ends.

), we’ll have one more thread discussing some concepts that don’t fit easily into any of the earlier threads. It’ll be a catch-all thread, starting out with a post or three about the 46 scheme and some discussion of nickel defenses. After that, I’ll probably open a Q&A/request thread to tie up any loose ends.

. So, I’ll just post some data after an extensive study of nearly every base 3-4 scheme since the mid-1990s. But first, some disclaimers.

. So, I’ll just post some data after an extensive study of nearly every base 3-4 scheme since the mid-1990s. But first, some disclaimers. .

.